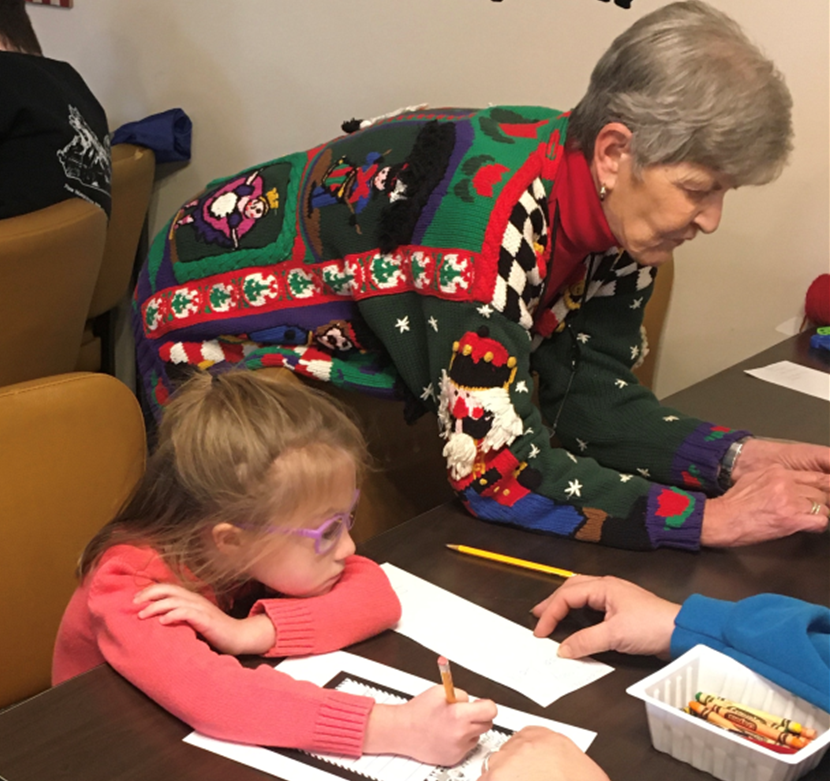

New train buffs Harper and Hayden Young run their Christmas presents on my (Ricky Bivins’) Valley Steel Lines layout.

Against a setting sun, a Union Pacific Railroad shipment of Canadian potash is crossing the Snake River on a 3920′ long viaduct. The Canadian Pacific Railway exchanges this and other traffic with the UPRR at the British Columbia border northeast of Spokane. The Joso Viaduct, opened on September 15, 1914, is reported to be the last major “hot rivet” railroad bridge built in the west, although verification is elusive. The bridge was the centerpiece of a new direct and more efficient U.P. line reaching into the Inland Empire. The rail is 240′ above the water. The bridge crosses the Snake near Starbuck, Washington, once an important UPRR town.

Building of the four notorious dams on the mighty Snake has flooded the region including some of the bridge piers. Concrete encapsulates the four tallest piers in the river due to higher water. This lake is the back pool of Lower Monumental Dam, about 20 miles downstream.

I used this picture and story in my “railfan Christmas card” in 2000. As you have seen by now, I do like sunsets and silhouettes. This shot was taken from the Lions Ferry State Park campground, obviously one of my favorite RV stops.

About a mile upstream is a recycled steel highway bridge. The state highway department took it apart, piece by piece, transported over a hundred miles and reassembled. That bridge and the ferry it replaced will be a subject for another day.

Greetings,

Hello again National Railway Historical Society, Western Kentucky Chapter members, and welcome to November. Cool (cold) weather is here!

We will have many things to discuss this month relating to upcoming events. The Christmas Show cancellation, Breakfast with Santa and the upcoming Christmas dinner. Also, we will make our second and final call for nominees for officers as our election will be held this month. Your attendance to these meetings and events is paramount. We need everyone’s collective energy to make things work.

As for elections, we had our first call for nominees last month, remember, everyone is eligible to hold an office. We have the offices of President, Vice President, Secretary, Treasurer and Chapter Representative. If you would like to hold an office, nominate yourself and don’t be bashful. I do not plan to run for president. I wish to pass the torch so to speak. So, speak up, be heard. YOU can be President!!!

Blair’s October UP 4014 program was a hit. Thanks Blair. The final photo contest has wrapped up. Jim will fill us in on same. Bill Farrell will have the final jacket order in hand, now we can all look sharp! I know Keith has been working on Breakfast with Santa, thanks Keith. Rich Hane suffered a fall this week. Not too serious I understand. We want to wish him a speedy recovery.

There will be more so be sure to attend. And again, step up and lead our Chapter in 2020!

Rick

November 13, 2019 – What a day!! I chased Union Pacific’s 4014 “Big Boy” from Prescott to Little Rock, Arkansas and couldn’t have asked for better weather! The cold really made the steam and smoke pop! Here we see 4014 as it departs Prescott early in the morning, after a slight delay to let two trains pass it. There’s just something about a steam locomotive when it pokes its nose out of a cloud of steam!

November 12, 2019 – Union Pacific Big Boy 4014 sits tied down at the Prescott, Arkansas depot, after its run for the day up the Little Rock Subdivision. Tomorrow morning it’ll depart at 9am CST for Little Rock where it’ll be on display till Friday morning before continuing it’s move back to Cheyenne, Wyoming. According to Wikipedia: The Missouri Pacific Depot of Prescott, Arkansas is located at 300 West 1st Street North. It is a 1-1/2 story red brick building, with a breezeway dividing it into two sections. One section continues to be reserved for railroad storage, while the other, the former passenger ticketing and waiting area, has been adapted for use by the local chamber of commerce and as a local history museum. It was built in 1911-12 by the Prescott and Northwestern Railroad, which interconnected with the Missouri-Pacific Railroad at Prescott. The line had passenger service until 1945.

The building is now known as the Nevada County Depot and Museum. Exhibits include area settlers, railroads, and military items from World War I, World War II, the American Legion, National Guard of the United States, 1941 U.S. Army maneuvers in Prescott. The depot building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

November 12, 2019 – Union Pacific’s “Big Boy” 4014 puts out a huge plume of steam in the cold November air as it departs Hope, Arkansas and heads north on the UP Little Rock Subdivision on its way to Prescott, AR where it will tie down for the night. I’m doing my first chase on the “Big Boy” today and tomorrow as it heads for Little Rock, AR.

According to Wikipedia: The Union Pacific Big Boy is a type of simple articulated 4-8-8-4 steam locomotive manufactured by the American Locomotive Company between 1941 and 1944 and operated by the Union Pacific Railroad in revenue service until 1959.

The 25 Big Boy locomotives were built to haul freight over the Wasatch mountains between Ogden, Utah, and Green River, Wyoming. In the late 1940s, they were reassigned to Cheyenne, Wyoming, where they hauled freight over Sherman Hill to Laramie, Wyoming. They were the only locomotives to use a 4-8-8-4 wheel arrangement: four-wheel leading truck for stability entering curves, two sets of eight driving wheels and a four-wheel trailing truck to support the large firebox.

Eight Big Boys survive, most on static display at museums across the country. This one, No. 4014, was re-acquired by Union Pacific and restored to operating condition in 2019, regaining the title as the largest and most powerful operating steam locomotive in the world.

September 2019 Photo Contest Results

We had a total of nine entries for the July 2019 chapter photo contest and the chapter members selected the winners during our October 2019 meeting.

Our last contest of 2019 will run from November 1-15th and the deadline for entries will be November 17th, 2019. Send your entries to me (no more than 2 per paid chapter member) at webmaster@westkentuckynrhs.org or jim@jimpearsonphotography.com by midnight on November 17th!

First Place, September 2019, West Kentucky NRHS Photo Contest – The East Chattanooga Station Platform during the night photo session of the 2019 L&N Railroad Convention at Chattanooga, Tennessee. – Photo by Keith Kittinger

Second Place, September 2019, West Kentucky NRHS Photo Contest – It’s a warm September afternoon on Lake Michigan in southern Wisconsin and number 4606 (nicknamed the Green Hornet) has pulled streetcar duty today for the Kenosha Transit System. Established in 2000, the two mile route through the downtown and park districts is one of Kenosha’s major attractions, hosting over 65,000 riders a year. – Photo by Chris Dees

Third Place, September 2019, West Kentucky NRHS Photo Contest – Saturday, September 28, 2019. NB at Crofton KY during the NRHS Chapter Picnic. – Photo by Rick Ricky Bivins

by Bill Thomas, editor

For 16 years now, I’ve watched the Morganfield branch (or what’s left of it to Dotiki Mine) host hundreds of coal trains bringing the powerful mineral topside to help power our country. Little did I know that when that last train rolled out from under the tipple it would signal the end of a 52-year stretch of mining in one facility. I was 4 years old when they started.

Since the late Dennis Carnal took me on a tour of western Hopkins and Webster counties almost 15 years ago, I’ve been fascinated with history of mining that contributed to the success of the branch from Madisonville to Diamond. Now as I drive school buses in the area and cross it at Happy Lane, Columbia School House Rd, Bernard St., Schmetzer’s Crossing, and SR 814, in see rust collecting on the shiny rails. The stacks of old ties bundled for re-use at home & garden centers and landscaping companies, the brand new asphalt crossings mentioned above speak of the volatile and often unexpected turns made in the coal industry these days.

No matter the reason, dirty coal, economic imbalance, or the continued battle against the coal industry in general, the trains are gone and now I wish I’d ventured out and taken more pictures. How we are lulled by the continuous sight of the passing train – thinking, “I’ll catch it next time when the weather is better or I have more time or when the light is better – or when I have my good camera instead of my iPhone.”

But, the great thing about being in a group like The Western Kentucky Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society is we are closely connected with those who often carry a good camera and are purposeful about getting those treasured photos. So here’s my tribute to those in the chapter who get the shots – good light or bad. Thank you for sharing your work on our website and social media outlets. Thanks for burning the gas and taking the time so the rest of us can enjoy the memories.

Above – NS #167 eastbound with the “yellow nose” SD70ACC #1800 leads the way towards Louisville just east of Depauw, Indiana on September 1, 2019.

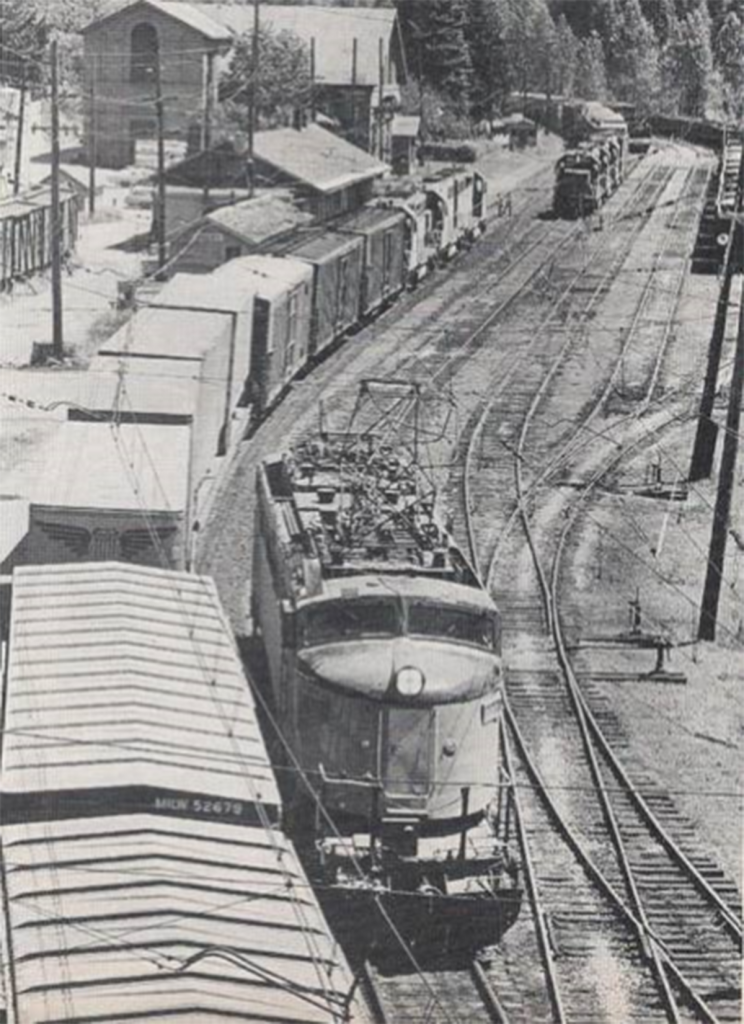

Left – Another scene that can never be replicated. This is Avery, deep in the Bitteroot Mountains of Idaho. You will recall the funny looking (not so) round house hanging over the river.

In its heyday, this is what Avery was all about. Exchanging steam or diesel locomotives for electric power facing a stiff climb up and through St Paul Pass Tunnel. Crews change here too.

In this busy scene the Little Joe in the foreground with it’s quad-headlight still on just uncoupled from the westbound up the track, and is heading for that funny looking roundhouse. The Joe was added at Harlowton, back some 440 miles across three major mountain ranges. From the control position in the Joe, the engineer operates all the power, even setting the diesels at idle on level ground, throttling up as needed. Soon a fresh crew will take the westbound on to points west terminating in Tacoma.

With the mainline cleared, a freshly serviced Little Joe will be placed on the point of the eastbound stopped at the depot. It’s new crew will shepherd the freight up the grade. Then it’s up the substation operator to supply the needed amps to get the job done. Substations like the one in the distance were located about every 30 miles.

This is the way I remember that day in July 1973 when I trekked through Avery with my wife and four kids in our new VW bus. They all remember the great ice-cream cones sold across from the depot.

Photo credit: Ted Benson featured in an Ed Lynch writing in Railfan & Railroad Magazine, October 1990

CSX #3245 is in charge of the CSX E321-18 as he is about to finish crossing the Tennessee River and enter Bridgeport, Alabama on a fine late sun evening. Photo by Bill Grady.

Clinchfield F-unit number 800 is seen on the Ohio Rail Experience’s DT&I North End excursion on Saturday, October 12, 2019 at Leipsic, Ohio. Hosted by the Indiana and Ohio Railroad, the excursion on the former Detroit Toledo & Ironton north to Diann Tower, Michigan allowed many rare mileage collectors to fill in a much needed segment of Henry Ford’s railroad. Photo by Chris Dees.

picnic fare and train-watching.