Back in the heyday of steam, several eastern railroads installed track pans.

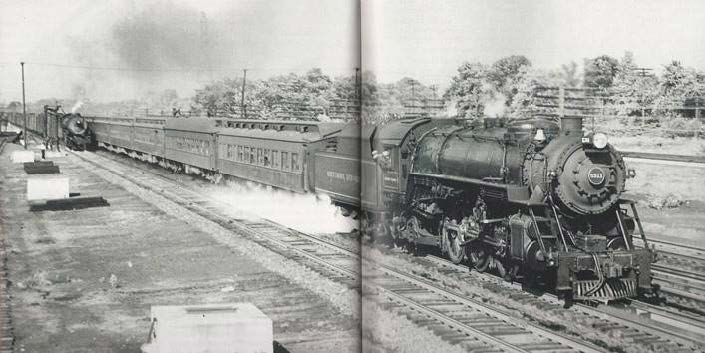

Having to stop for water was the nemesis of steam. This picture clearly illustrates the advantage. I would have preferred an image without the centerfold, but I’ve never seen a picture of trains, side-by-side taking water by track pan and water plug.

The passenger train is Baltimore & Ohio’s Diplomat rushing to Washington and St Louis in June 1944. At track speed, on a signal from the engineer, the fireman engages and air-operated scoop that fills the tank in short order from the pan between the rails.

It’s easy to see the wisdom here. The tender has an oversized coal bunker, at the expense of a limited water capacity. The Diplomat and other “scoop” trains can fly past those water plugs, saving time, not to mention the wear and tear, and energy to stop and restart a train. Lesser trains and most freights stop periodically for fuel and water, such is the case of the Reading Railroad freight train in the distance.

Installation of track pans required table-top level right-of-way. The New York Central’s 20th Century Limited on its nightly run from New York City to Chicago scooped water dozens of times, but only stopped for coal once for the entire trip. In the days before air-conditioned travel, it was wise for passengers to make sure the windows were closed at these locations, especially near the front of the train. Spray swirls from the scoop under the tender, and you can see the sky reflecting off the water in the pan at the front of the locomotive.

Gary Ostlund Credits: Ralph E. Hallock photo as seen in Classic Trains Magazine, Spring 2006

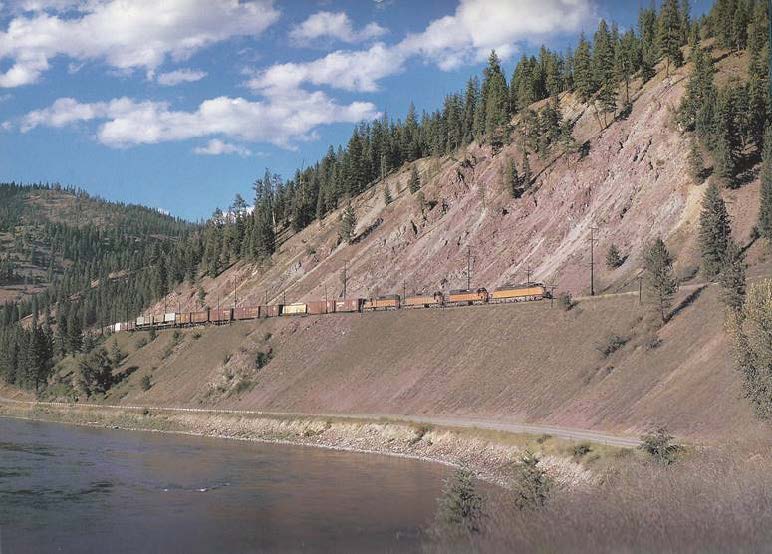

Western Montana is tough to beat for scenery, and great territory for railfans. Witness this eastbound Milwaukee freight near Tarkio. Even a large train can look rather insignificant against a rugged mountainous backdrop. A “little Joe,” one of twenty built by General Electric for Joseph Stalin’s Russia in 1948 leads three much newer GM built diesels.

The Joe packs 5,500 horsepower, each diesels add 3,000 more. The “motor” (electric engines are motors in RR lingo), was added for the climb through the Bitterroots, the Rockies and the Belt Mountain ranges. The diesels will run through to Chicago.

Little used former US highway 10 is seen below the train. The Clark Fork River begins near Butte and drains into Lake Pend Oreille (Ponderay) in Idaho. The river, continues through N.E. Washington as the Clark Fork or the Pend Oreille River (depending on which map you use), to the Columbia, just inside Canada at a town appropriately named “Boundary.”

Out of the picture and across the river is Interstate 90 and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe rails of the former Northern Pacific. The NP and Milwaukee crews could see each other for many miles passing through Montana. In many places they were side-by-side, somewhat like double-track.

This scene captured by Robert F. Wilt in July 1973, graced the Milwaukee Railroad Historical Association calendar for June 1992. Thirteen months later the electrics dropped their pantographs for the last time. Seven years hence the railroad ceased to exist west of Minnesota. – Gary Ostlund

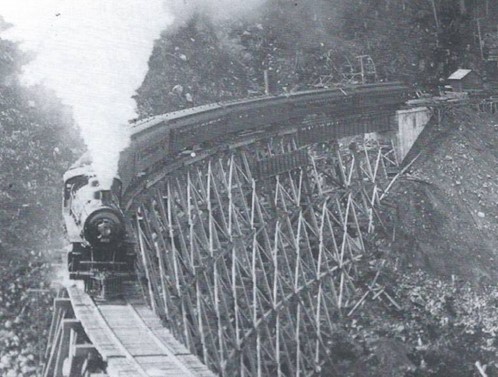

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.