I visited Wally Watts and surprised him with chocolate and a balloon on his 91st birthday! September 18, 2021.

Ricky Bivins

Photos from the Pennyrail Newsletter

I visited Wally Watts and surprised him with chocolate and a balloon on his 91st birthday! September 18, 2021.

Ricky Bivins

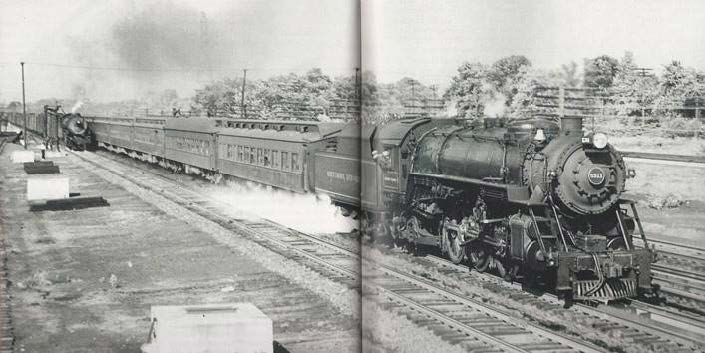

Back in the heyday of steam, several eastern railroads installed track pans.

Having to stop for water was the nemesis of steam. This picture clearly illustrates the advantage. I would have preferred an image without the centerfold, but I’ve never seen a picture of trains, side-by-side taking water by track pan and water plug.

The passenger train is Baltimore & Ohio’s Diplomat rushing to Washington and St Louis in June 1944. At track speed, on a signal from the engineer, the fireman engages and air-operated scoop that fills the tank in short order from the pan between the rails.

It’s easy to see the wisdom here. The tender has an oversized coal bunker, at the expense of a limited water capacity. The Diplomat and other “scoop” trains can fly past those water plugs, saving time, not to mention the wear and tear, and energy to stop and restart a train. Lesser trains and most freights stop periodically for fuel and water, such is the case of the Reading Railroad freight train in the distance.

Installation of track pans required table-top level right-of-way. The New York Central’s 20th Century Limited on its nightly run from New York City to Chicago scooped water dozens of times, but only stopped for coal once for the entire trip. In the days before air-conditioned travel, it was wise for passengers to make sure the windows were closed at these locations, especially near the front of the train. Spray swirls from the scoop under the tender, and you can see the sky reflecting off the water in the pan at the front of the locomotive.

Gary Ostlund Credits: Ralph E. Hallock photo as seen in Classic Trains Magazine, Spring 2006

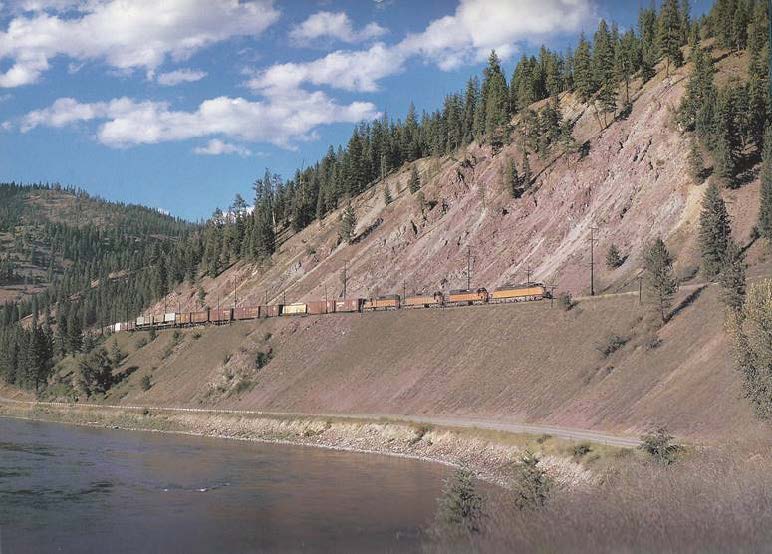

Western Montana is tough to beat for scenery, and great territory for railfans. Witness this eastbound Milwaukee freight near Tarkio. Even a large train can look rather insignificant against a rugged mountainous backdrop. A “little Joe,” one of twenty built by General Electric for Joseph Stalin’s Russia in 1948 leads three much newer GM built diesels.

The Joe packs 5,500 horsepower, each diesels add 3,000 more. The “motor” (electric engines are motors in RR lingo), was added for the climb through the Bitterroots, the Rockies and the Belt Mountain ranges. The diesels will run through to Chicago.

Little used former US highway 10 is seen below the train. The Clark Fork River begins near Butte and drains into Lake Pend Oreille (Ponderay) in Idaho. The river, continues through N.E. Washington as the Clark Fork or the Pend Oreille River (depending on which map you use), to the Columbia, just inside Canada at a town appropriately named “Boundary.”

Out of the picture and across the river is Interstate 90 and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe rails of the former Northern Pacific. The NP and Milwaukee crews could see each other for many miles passing through Montana. In many places they were side-by-side, somewhat like double-track.

This scene captured by Robert F. Wilt in July 1973, graced the Milwaukee Railroad Historical Association calendar for June 1992. Thirteen months later the electrics dropped their pantographs for the last time. Seven years hence the railroad ceased to exist west of Minnesota. – Gary Ostlund

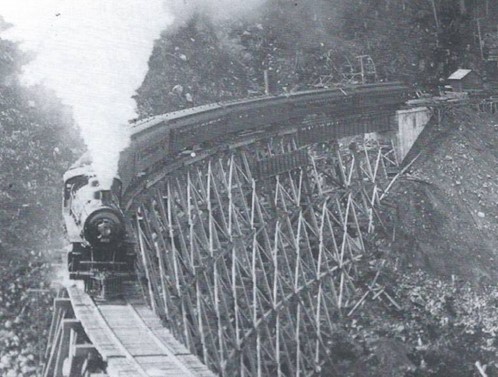

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

September 9, 2021, and CSX GP38-2 2806 arrives in Mitchell, Indiana with a rather sparse two-car local J780. The crew will tie down for the day and hopefully have m o r e L e h i g h Cement loads for the eastbound trip to North Vernon the next day.

Consolidated Grain and Barge GP9 6140 shuttles CSX covered hoppers for loading at Olney, Illinois on

September 8, 2021. Later in the day CSX AC4400CW 231 and ES44AH 761 will haul the train east to

Vincennes, Indiana and then points south. – Photo by Chris Dees

At JO Tower in Seymour, manifest Q688 (Louisville to Indianapolis) waits for the track gang and signal department to finish up PTC installation work on September 9 , 2021. Once cleared, the train will continue its northbound journey over the Louisville & Indiana Railroad. Photo by Chris Dees

Below, a UP Northbound Stack Train is on a roll through Scott City, Missouri on the

morning of August 29, 2021. The last shot of UP 4014 was made as it crossed over the Kaskaska

River just north of Chester, Illinois on the afternoon of August 29, 2021 Photos by

Bill Grady Photo by Bill Grady

The time is 12:30 PM on October 13, 1949. We’re inside Mission Tower, half a mile out of Los Angeles Union Station, watching Southern Pacific train 4, the Golden State (left) and Santa Fe 20, the Chief, departing simultaneously for Chicago. It looks like a race, but it’s not really much of a contest: The Chief, running on Santa Fe all the way for 2,224 miles, will beat the Golden State (2,268 miles on the SP and Rock Island) to the Windy City by about 7-3/4 hours.

The Chief will cross Cajon Pass to Barstow and shoot east across northern Arizona to Albuquerque, NM, then northeast over two mountain passes, and cut through the southeast corner of Colorado. After a stop in Dodge City and a few others, it will aim for Kansas City. Cutting through the SE corner of Iowa, crossing the Mississippi River, it will visit some cities in Illinois before arriving at Dearborn Station, one of seven railroad stations in Chicago.

The Golden State exits California near Yuma, does a bee-line for El Paso, then NE through New Mexico to Tucumcari. There the Rock Island takes over touching a bit of Oklahoma, slicing through Kansas to Topeka and on to Kansas City. Then the GS treks through a corner of Iowa, zips through the Quad Cities. On through the corn fields of Illinois, it completes its trek at LaSalle Street Station, only a few blocks from Dearborn and the Santa Fe.

There were other passenger trains that competed head-to-head, mainly the New York Centrals 20th Century Limited and Pennsy’s Broadway Limited. They raced out-of-Chicago, on parallel tracks, for many miles in their quest to get their patrons to New York City, fast. That daily race was a little more even-handed. The New York Central route to the Big Apple was 960.9 miles, with mostly water level terrain. The Broadway’s routing was only 908.2 miles, but included scaling the Appalachian Mountains in Pennsylvania. Wikipedia states that both of these luxury trains completed their task in about 16 hours. The green hat crowd and the red hatters probably will never agree on that.

Credits: First paragraph verbatim in Classic Trains Magazine, Spring 2021

Submitted by Gary O. Ostlund

I spotted this little jewel at Holiday World Splashing Safari last month as I aided our Youth Minister on a Youth outing. After researching (Googling) it, I found it was the first ride in Santa Claus Land Railroad (later to be Holiday World). The locomotive was restored and placed on display to celebrate the park’s 70th birthday this year. You can watch a time-lapse video on YouTube of the painting: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kNdeiWlIej8. Ed. Bill Thomas

The Missouri River is the longest river in North America. Rising in the Rocky Mountains of western Montana, the Missouri flows east and south for 2,341 miles before entering the Mississippi River north of St. Louis, Missouri. The river drains a sparsely populated, semi-arid watershed of more than 500,000 square miles, which includes parts of ten U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Although nominally considered a tributary of the Mississippi, the Missouri River above the confluence is much longer and carries a comparable volume of water. When combined with the lower Mississippi River, it forms the world’s fourth longest river system.

Matthew Herson climbed this hillside in the Fall of 1967 to capture this scene downriver from Three Forks, Montana, where the Gallatin, Jefferson, and Madison rivers converge whereupon — America’s longest river is born. If you add the length of the Madison River, then nearly the first 400 miles of this system travels northwest and northeast, then east, before trekking mostly south to meet the mighty Mississippi.

The train is the Northern Pacific’s Mainstreeter going downriver, westbound to the coast. Across the river is the track of the Milwaukee Railroad. An anomaly has the NP’s westbound trains going downriver, while the Milwaukee westbounds go upriver. Sounds impossible, but it’s all in the routing of their tracks.

Later when asked “if he saw any rattlesnakes,” the place is full of them. Thanks for the advance notice…. Credits: First paragraph verbatim – Internet. Herson’s photo skills were featured in the latest Mainstreeter, the NP Railway Historical Associations quarterly magazine. Submitted by Gary Ostlund

The Norfolk Southern heritage unit, NS 8114 at Princeton, IN. – Photos by Steve Gentry

Steve Gentry caught two NS freights waiting to enter the yard at Princeton, IN, May 8, 2021. – Photo by Steve Gentry

I went out looking for a military train that was south bound and I ran out of light. I did manage to get a north bound mixed freight and a south bound coal train. – Photography by Bill Farrell

Steve Gentry spotted this WFRX GP15 March 9, 2021, it was sitting on the site of the old L&N station in Evansville. The old L&N station was located on Fulton Ave close to Ohio Street. It has a fresh coat of paint. The track it was sitting on services a couple of downtown Evansville locations. Apparently 560 is being assigned switching duties at Berry Plastics in Evansville.

Ricky Bivins shot all but one of these from his home in Mortons Gap, KY