Spotting features: photo- Kalmbach Media

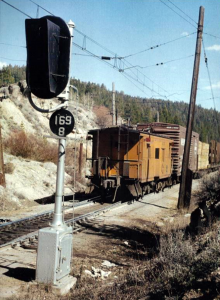

This is not your ordinary well-manicured railroad R-O-Way (city park..?) The roadbed is nicely maintained, the ballast is neatly dressed, (little attention is given to most land abutting RR ROW.) The crossing arm is down as it should be, and we must assume the lights are flashing alternately. (The crossing arms might be short, as there are no counter-balancing weights. Perhaps this is a walking trail (in that park) rather than a highway crossing.)

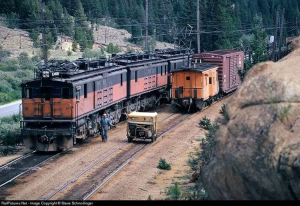

Orange-tipped gas line marker (some rights-or-way are used for buried utilities, phone lines mostly, but this appears to be a line crossing under the railroad). Rusty – welded, protective barrier made of used “rail.” To me that means the railroad probably fabricated and placed it there. (is it protecting a fire Hydrant.? Seems to be in an unusual location, so close to the rails, yet there is foliage). Graffiti-laden well-cars. (the closest being an articulated unit, then a solo, followed by a 5-set, the fifth segment in the shade. Articulated units share a wheel-set between each car.)

Wally-world has gone modern (those containers have been extended to the legal limit of 53 feet, also there just may be an element of “promotion” with such dominant placement.) It’s Spring or Summer (who can identify the red flowers..? Can anybody ID the location?)

My friend and advisor, Dave Sprau correctly pointed out that this was a promotional display kicking off new logistics within the Walmart organization.

– Gary O. Ostlund