The Missouri River is the longest river in North America. Rising in the Rocky Mountains of western Montana, the Missouri flows east and south for 2,341 miles before entering the Mississippi River north of St. Louis, Missouri. The river drains a sparsely populated, semi-arid watershed of more than 500,000 square miles, which includes parts of ten U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Although nominally considered a tributary of the Mississippi, the Missouri River above the confluence is much longer and carries a comparable volume of water. When combined with the lower Mississippi River, it forms the world’s fourth longest river system.

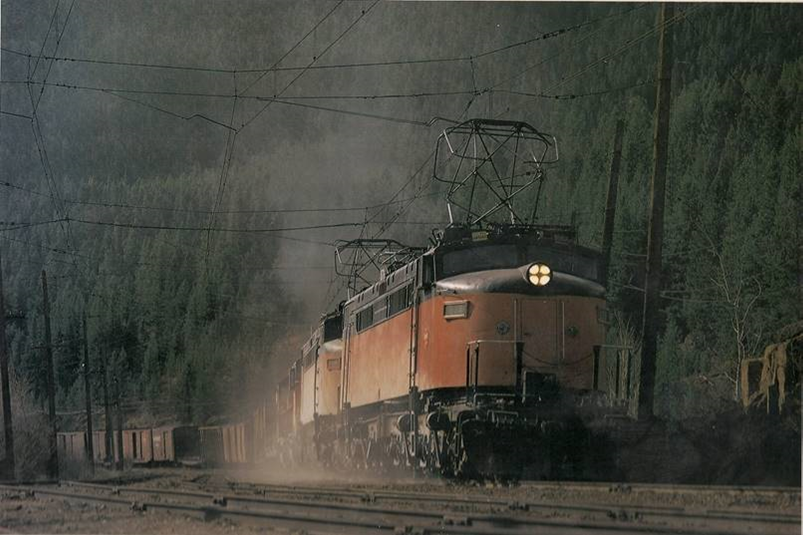

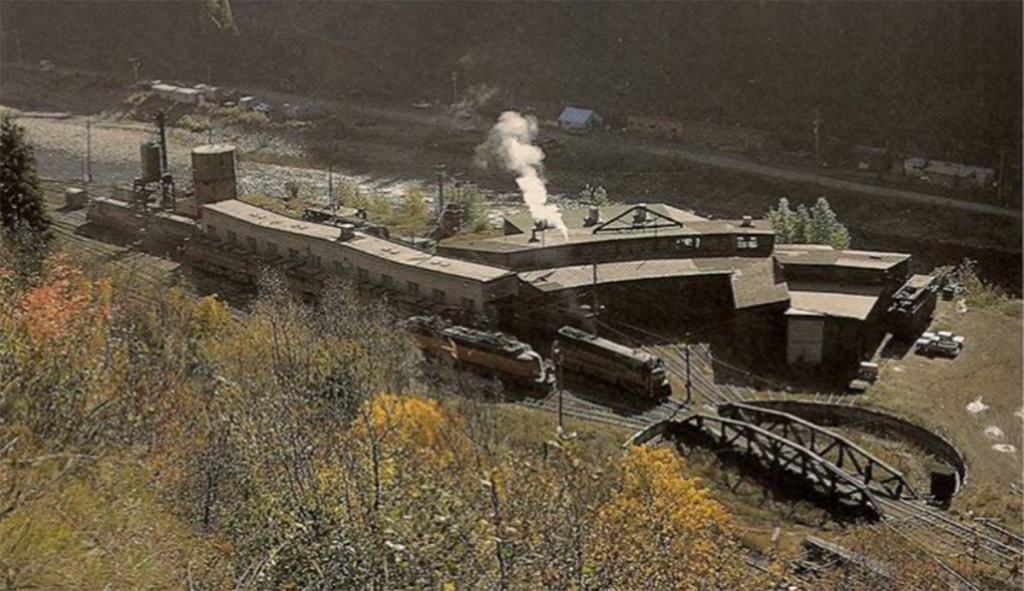

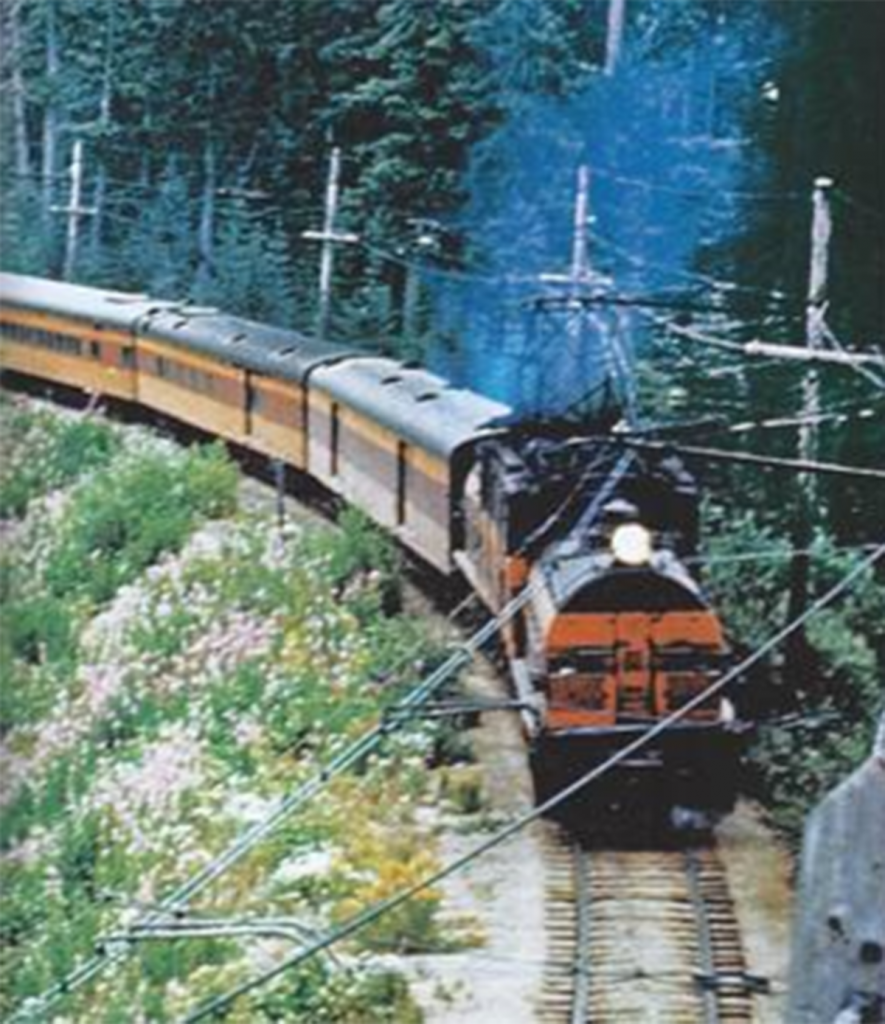

Matthew Herson climbed this hillside in the Fall of 1967 to capture this scene downriver from Three Forks, Montana, where the Gallatin, Jefferson, and Madison rivers converge whereupon — America’s longest river is born. If you add the length of the Madison River, then nearly the first 400 miles of this system travels northwest and northeast, then east, before trekking mostly south to meet the mighty Mississippi.

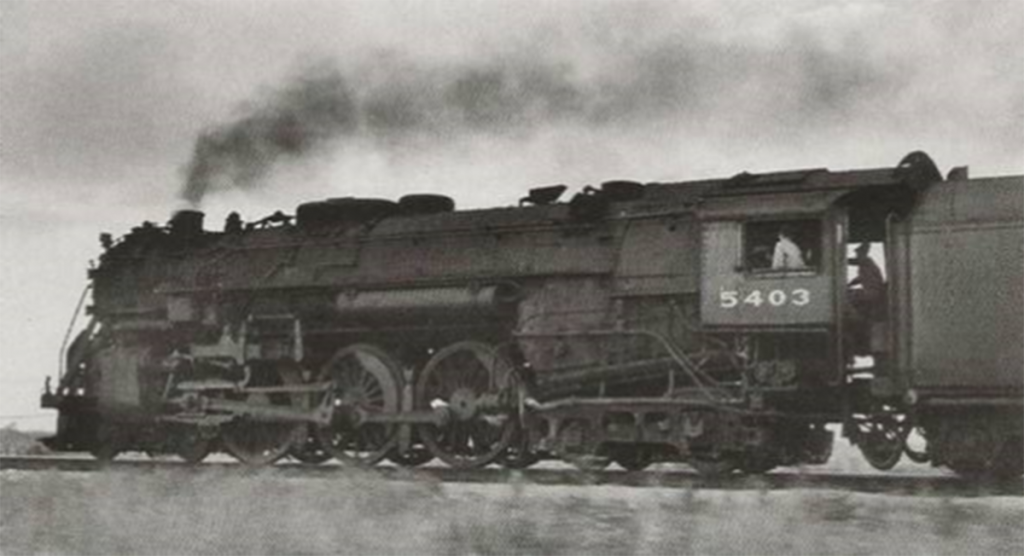

The train is the Northern Pacific’s Mainstreeter going downriver, westbound to the coast. Across the river is the track of the Milwaukee Railroad. An anomaly has the NP’s westbound trains going downriver, while the Milwaukee westbounds go upriver. Sounds impossible, but it’s all in the routing of their tracks.

Later when asked “if he saw any rattlesnakes,” the place is full of them. Thanks for the advance notice…. Credits: First paragraph verbatim – Internet. Herson’s photo skills were featured in the latest Mainstreeter, the NP Railway Historical Associations quarterly magazine. Submitted by Gary Ostlund