The winners for our July 2024 photo contest were Bill Grady 1st Place and Bill Grady for 2nd! Congratulations Bill and our next contest runs the month of September 2024! Entries due to Jim Pearson by midnight on October 7th.

The winners for our July 2024 photo contest were Bill Grady 1st Place and Bill Grady for 2nd! Congratulations Bill and our next contest runs the month of September 2024! Entries due to Jim Pearson by midnight on October 7th.

The winners for our May 2024 photo contest were Ricky Bivins for 1st Place and Bill Grady for 2nd! Congratulations to you both and our next contest runs the month of July 2024! Entries due to Jim Pearson by midnight on August 7th.

Stevens Pass in Washington State provides great vistas for the railfan, whether on the east slopes like

this scene, or up the west side. This is former Great Northern mainline with a westbound freight looping along Nason Creek through Gaynor Tunnel. The 8-mile Cascade Tunnel is about a mile ahead. Noted

northwest railfan Ben Bachman captured this stunning shot from a switchback laden US Forest Service trail leading to Rock Lake in 1995.

In 2001 yours truly attempted the same. Needless to say Ben had a better camera, with much better results. The exercise and fresh air was nice. But not all was lost, I spent the night very near trackside in the trees just across the bridge in the upper left of this scene. This was one of those camp trips where sleep is sporadic. Hot coffee and a bacon and cheese omelet soothed things nicely in the morning. In over reaction to 911 the Burlington Northern Santa Fe has blocked access to the well hidden road leading down to my semi-private campsite. Nothing stays the same. Pacific Rail News May 1996.

Former CSX Transportation B40-8 5964 sits outside at the West Tennessee engine house in

Jackson, Tennessee as new paint is being applied. Photo by Chris Dees on July 5, 2024.

West Tennessee power reflects in the puddles from the previous evening’s rain at the Jackson,

Tennessee yard. Photo by Chris Dees on July 5, 2024.

A Fracking Paducah Geep in Wisconsin – With all the frac sand mining in western Wisconsin it’s no

surprise to see industrial switchers at some of the facilities. On May 25, 2024, a former ICG GP10, 4613, is seen east of Tomah, WI. This old girl has done service for her country in the U.S. Army and now is a lease unit owned by Robert Riley’s Rock Island Railroad, as noted by the RILX reporting marks. Photo by Chris Dees.

All Aboard the Borealis – On Sunday, May 26, 2024, the eastbound Amtrak Borealis prepares for departure at the Saint Paul, Minnesota, Union Station. The new Borealis service – a partnership between Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, CPKC and BNSF – provides a second option for daily Amtrak service in this part of the Midwest. Service started just six days earlier on Tuesday, May 21, 2024 and ridership is strong. Photo by Chris Dees

Parked at Portage – Two un-rebuilt Canadian Pacific SD40-2 units, 6043 and

6025, bask in the sunlight at Portage, WI on May 25, 2024 as they await their next

assignment. Photo taken by Chris Dees from the northbound Amtrak Borealis (new

service from Chicago to St. Paul) that just launched four day earlier on May 21, 2024.

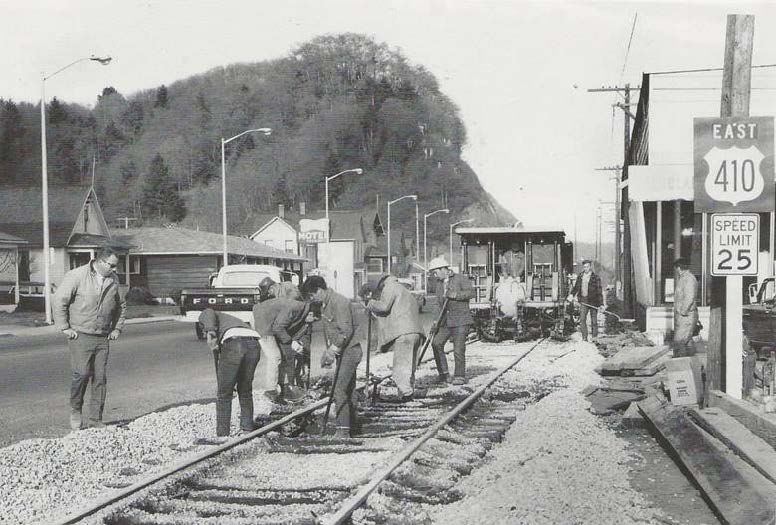

I was the Army Recruiter there from 1963 to 1968. The party-line was that this was a water diversion issue, but anyone that traveled that way when a train was passing took their life into their hands. The roadway behind the foreman with the Ford pickup heading east (out of town) is a two-lane and sole entry into Aberdeen from the east.

The way those boxcars swayed back and forth; I don’t know how they kept on the track. Most folks would not pace those outbound trains, as the rolling stock was in what would have been an adjacent traffic lane were it a four-lane highway.

On outbound trains many if not most of the boxcars full of shakes and shingles had no doors. Clearly, the railroad saved their, newer rolling stock for cleaner products that needed all-weather protection. Doorless boxcars full of raw wood products seemed to travel safely to their customers far away. A series of 4×4 lumber stock from floor through the holes in the roof kept the bundles safely aboard. The shakes and shingles would arrive safe, having most likely been rained upon a few times.

They are, after all, roofing material.

In my five years there I never heard of an incident. Luck…? Only the Northern Pacific

Railway used this entrance to the twin cities of Aberdeen and Hoquiam. The Union Pacific and Milwaukee also entered from the east, but on the southern side of a major river valley coming through Cosmopolis and South Aberdeen. They crossed the river on a swing bridge about a half mile behind the photographer. Today this line is the only rail entry, now serviced by the short-line Puget Sound and Pacific Ry. – Photo by Dell Mulkey

Tidbits on the life of a railroader. Early in the 20th century (and before the various “Safety First” campaigns that we still see today), a dozen railroaders — on average died on the job every day. On any given day, tens of thousands more were injured or maimed.

That was often brought home by the fact that few conventional insurance companies would write policies for railroaders — their jobs were considered too risky. So, railroaders set up their own group insurance plans and mutual benefit associations. An industrial pension program so that employees could expect to retire (rather than work until they died) was largely a railroad innovation. The first plans emerged in the early 1880s and led to the creation of the Railroad Retirement Board in 1934, which was the model for the Social Security Act, just a year later.

Hundreds of thousands of railroaders worked in jobs that took them away from their homes and families. Sometimes they enjoyed networks of boarding houses, railroad YMCA’s, beaneries, and places of entertainment and commercial affection. At other locations, the away-from-home accommodations could be threadbare or downright deplorable. And then, the names. For everyone from the president on down, official railroad documents generally identified the employees by a sterile two initials and surname, (J. T. Blow). Yet no group of industrial workers embraced nicknames more than railroaders. There was always a few Butches, a Nookie, Boogie, Shotgun, Skeeter, Barney, Screwdriver, Speedy, and all sorts of fellows who, for one reason or another, went by some alternate version of their given names. All of which speaks to a larger truth. Despite the hazards and demands, railroaders were proud of their work. You would hear variations of this theme many times: “I hate the company but love the work,” or, “I can’t believe they pay me to do this.”

A friend of mine in Butte, Fred Coombes was #1 seniority in the Rocky Mountain division, and a fellow church member. He knew I was an avid railfan, but straight-laced as he was, he never even let me up in the cab the many times I saw him hooking up and trekking over Pipestone Pass. He and I both respect the Rules. He retired when the electrics ended in ‘74, and moved to Seattle with his wife of many years. I once asked him why as #1 on engineer’s seniority roster that he didn’t bid on some glamorous hotshot freight-run. With a twinkle in his eye, he stated: “I sleep in my own bed every night.”

This rather interesting switch stand is on the ex-C&NW West Allis, WI to New Berlin, WI spur. UP runs twice a week for a couple of industries in the New Berlin area. Interestingly enough the switch is out of service and the throw mechanism, frog, etc have long been removed. – Photo by Chris Dees

Spring is in the air and the cold temperature are lifting! We recently rolled No. 576 outside to remove the side rods. It’s always a treat to see the locomotive in the natural light! Work continues in the shop as we inch closer and closer to seeing Music City’s locomotive back under steam. Recent projects include

completing repairs to the firebox, installation of hundreds of flexible and rigid stay bolts, and disassembly of the tender trucks. Submitted by Bill Farrell.

Members of the WKNRHS enjoyed an outing to the Kentucky Railway Museum in New Haven,

Kentucky, this past Saturday, April 13, 2024.

The winners for our January 2024 photo contest were Bill Grady for 1st 2nd, Place. Congratulations to you Bill and our next contest will run the full month of May 2024!

Other March 2024 Contest Entries

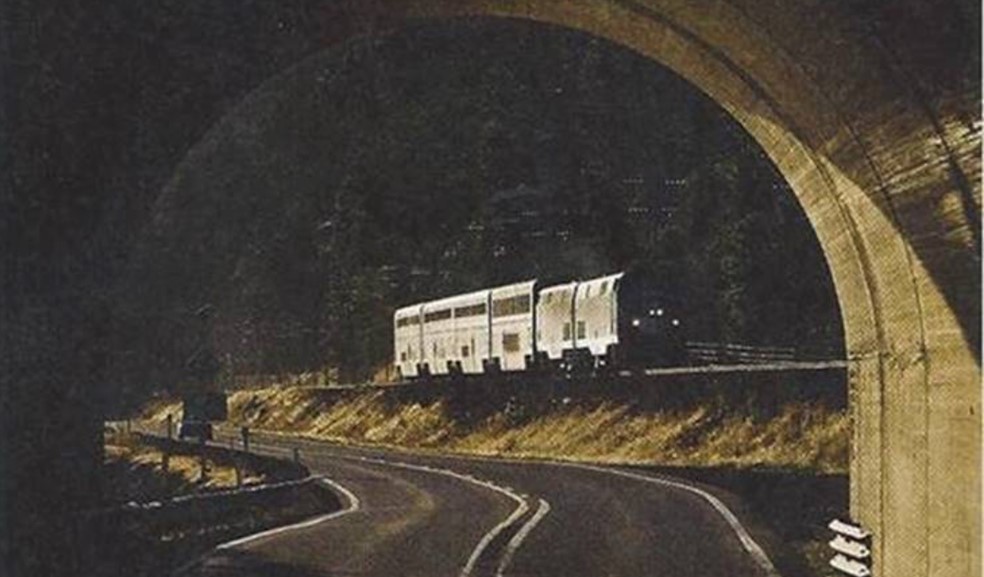

The Columbia River Gorge is a terrific place to watch and chase trains. Both sides of the river host major rail lines, the former Spokane, Portland & Seattle, now BNSF on the Washington side, and Uncle Pete, the Union Pacific across the pond in Oregon.

It’s also a haven for other outdoors persons, particularly bicyclists. Oregon’s Interstate 84 frowns on bicyclists, so they flock to Washington’s two-lane State Highway 14. SH 14 shares the narrow gorge with the railroad involving an array of tunnels as seen above.

The problem: look as the guard rail at the tunnel entrance, and you’ll see the roadway has no room for bikers, or pedestrians. They compete for space with cars, 18-wheelers in these tight tunnels, six times in about 15 miles. At least they are short, averaging 500′ in length, but some have a gradual curve adding to the rise in blood pressure…

To enhance safety, the state installed push-button flashing lights with a sign: “Bikers Ahead.” Having navigated this maze several times, I can tell you that nearly no one slows down, so you look back and wait for a pause in the traffic, then pedal like your life depends on it. It does….!

But, I’d do it again, the trains, river, steep cliffs, eagles and ospreys, Mount Hood in the distance, all make it worth it. That’s the Portland-to-Spokane connection for Amtrak’s Empire Builder. It left Portland about an hour earlier, late afternoon. Usually a whole fleet of freights is soon to follow. – Gary Ostlund

Credits: Pix by John Ryan, as seen in TRAINS Magazine, September 2011

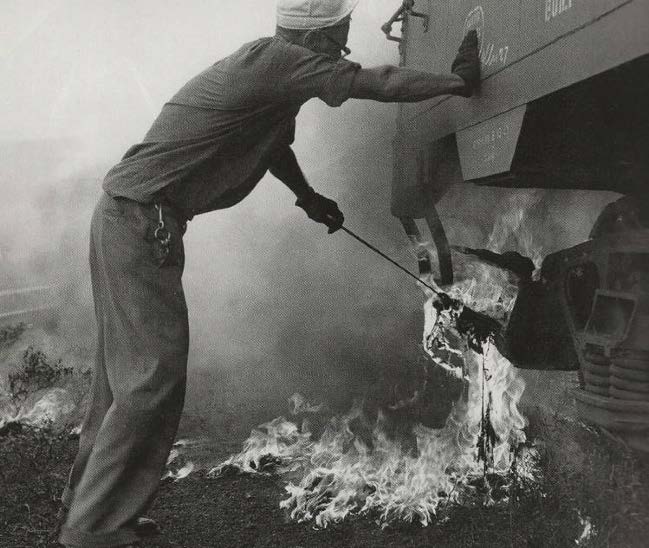

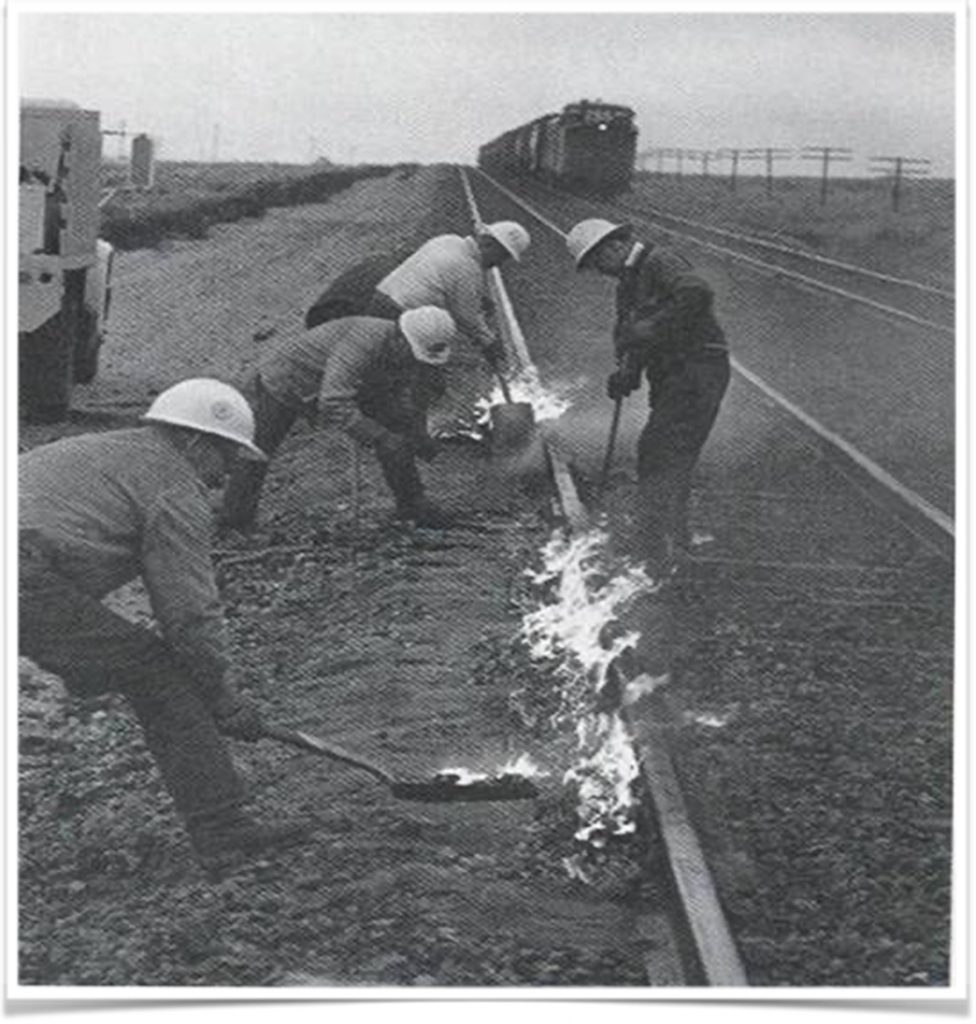

With a westbound freight receding into the horizon, a Santa Fe section crew at Walapai, Arizona, resumes its work, connecting cold rail. The men have ignited scraps of wood to expand and lengthen the cold steel rail on a rainy December 1977 afternoon.

They have replaced this rail. If you look closely, this is jointed rail, 39 foot lengths unlike continuous welded rail you would find in mainline operations today. Why 39′ rather than a nice round number like forty? Two reasons: “That’s the way they always were, but more importantly, they fit nicely on relatively those short forty-foot flat cars of years gone past.”

You can see the outside fishplate and joint at the feet of the worker standing inside the rails holding a long open end wrench. When the rail expands and the holes line up, his partner will slide in two bolts through a fishplates sandwiching the rail ends. He’ll then place a washer and square-headed nut, whereupon the open-ended long handled wrench will cinch it down tight.

Those joints provided the clickety-clack that was music in years past whether in coach or Pullman sleeping cars. Today the welded rail gives a better ride, is safer, quieter, less maintenance intensive, but I still like the clickety.

photo credit: Dave Stanley as seen in TRAINS 100 Greatest Railroad Photos

Submitted by Gary Ostlund

Milwaukee, WI – Considered a historic attraction, the North Shore Bank Safari Train is the Milwaukee County Zoo’s oldest and most popular ride. And this year, the Train’s No. 1916 and No. 1924 steam locomotives (engines) will leave the station for the last time, transferring to the Riverside & Great Northern Preservation Society (R&GN) in the Wisconsin Dells. The No. 1916 engine will depart on April 1, followed by the No. 1924 engine on Oct. 31. The sale of the steam engines supports the Zoo’s mission of conservation and sustainability and aligns with Milwaukee County’s vision of becoming the healthiest county in Wisconsin. The Train will continue to operate as usual with the Zoo’s No. 1958 and No. 1992 diesel engines. -submitted by Chris Dees

A detouring Lincoln Service train uses the 5-mph connecting track between Metra’s Rock Island District and the St. Charles Airline on June 16, 2007. The raised bridge in the background has been out of service for about 50 years, but demolishing it is too expensive. Bob JohnstonBeneath a blinding headlight, four locomotives advance stiffly along a tight connecting track as

the rails squeal in protest. A dark figure emerges from a pickup truck waiting in the gathering

darkness, swinging a grip onto the lead unit’s pilot before mounting the steps. Throttling up, the

long train accelerates into the night, leaving its usual route behind for the unobstructed trackage of

another railroad. The “dark figure” was a pilot engineer.

Detours are nearly an everyday experience. Wrecks, scheduled maintenance work,

washouts, mudslides — all of these obstacles may cause trains to detour. Although railroads have

a long history of competition, they decided long ago that it made sense to cooperate in times of

crisis. To provide a contractual framework for such cooperation, the American Railway

Association in 1905 adopted a “Standard Form for Detour Agreement” which railroads could sign

to govern emergency operations over each-others lines.

Under the Detour Agreement, the railroad desiring to detour its trains (called the Foreign

Company) notifies the railroad it wants to use (the Home Company) why it needs to detour, what

part of the Home Company’s lines it wants to use, how many trains it wants to detour, “and such

other information as may be required by the Home Company.” The Home Company has complete

discretion to accept or refuse offered detours. As a practical matter, though, railroads rarely refuse

detour movements, because no carrier ever knows when it will need the favor returned.

The Foreign Company assumes all risks of liability arising out of the detour operations. Its

responsibility is absolute, even if the Home Company is clearly at fault. Another cost a detouring

railroad must pay is the trackage-rights charge imposed by the Home Company. Since 1978, the basic charge in the Detour Agreement has been $9 per train-mile. To that charge, the Home

Company adds the cost of crews, fuel, train and engine supplies, repairs, and locomotives provided

to detoured trains.

There’s one operator that isn’t bound by the Detour Agreement — Amtrak. The passenger

carrier has the right, under the Rail Passenger Service Act and its contracts with the major railroads,

to detour trains for incremental costs, meaning the specific cost of operating the detoured train

without any profit element.

Amtrak is also insulated to some degree from the costs of using railroad crews by the

unusually long crew districts it has established for passenger operations. However, Amtrak still

must use railroad pilots when its crews are not qualified to operate over unaccustomed territory

and rent locomotives when its own units can’t read the host railroad’s cab signals.

This article, originally entitled “When trains must leave home,” appeared in the November 1993 issue. [ The above are excerpts from a much longer array. / Source for example below is from the Northern Pacific Railway Historical Association Mainstreeter, Volume 19, No. l, Winter 2000. GOO ]

Addendum: A Real Life Example (with a lot of disappointed railfans)

From 1956 to 1968 the Northern Pacific Railway hosted what was called “Casey Jones Excursions, ” initially using steam hauled vintage passenger cars in Washington state. The NP was uniquely qualified to do this, in that western Washington was full of branch-lines. These excursions were always on Sundays when traffic on those lines was light or non-existent.

Steam locomotives were being sidelined by the industry-wide conversion to diesel, and adequate passenger cars were sitting idled in coach yards. To say that great times were had by all would be an understatement. These excursions were always sold-out. Labor Day 1965, a fully loaded Casey Jones Excursion was heading across the Cascade Mountains destined to the Ellensburg Rodeo, a popular end-of-summer festival. Ahead of them a freight derailed inside the 2-mile Stampede Pass tunnel shutting down the line. The excursion was sidelined in the small mountain town of Lester. The hamlet found its population increased by one-thousand, to the delight of the village grocer and barkeep. The excursion manager immediately began negotiations with the NP dispatcher for a detour rerouting over the Milwaukee Road’s Snoqualmie Pass line. The verdict was no. A detour would have involved returning half way back down the mountain, and trekking on a foreign-lines “less than stellar branch line” to the Milwaukee main-line over Snoqualmie. Having read the detour agreement policy above, it is understandable. These excursions for the most part, paid for themselves, but the railroad was not going to gamble on the potential costs of a derailment on foreign rails. The railway gracefully refunded

the charter money.

Gary O. Ostlund