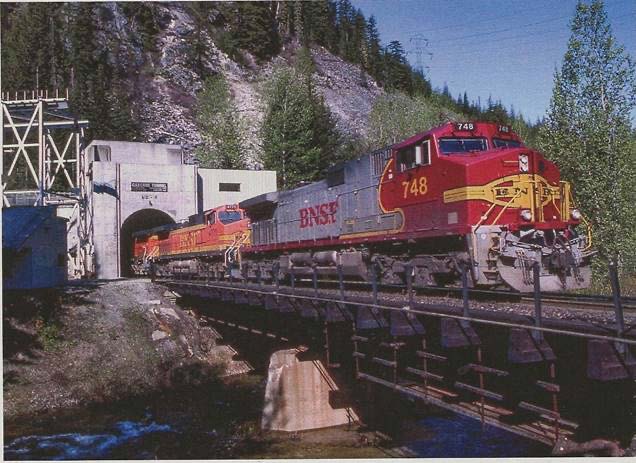

Credits: East portal photo by Alex Mayes. Submitted by Gary Ostlund.

In 1956 when the fully dieselized Great Northern Railway turned off the juice on their electrified line over (actually under) the Cascade Mountains in Washington state, they thought their trouble with smoke and fumes was over. Wrong..! The 8-mile tunnel under Stevens Pass opened in 1929 had been utilized by electric powered trains from day-1.

With the introduction of diesel-power the tunnel had to be purged of diesel fumes after each eastbound train. The grade inside the tunnel eastbound is fairly steep, 1.57%. The long tunnels I know of are either ascending one direction or the other. Some ascend from both portals to a high point in the middle. All this is in the interest of drainage.

Fast-moving passenger trains can negotiate the tunnel successfully, but when slower freight locomotives tried it, operating problems became immediately apparent. Tremendous heat generated by the exhaust gases of slow moving east-bounds raises air temperatures dramatically. The trailing unit of a multiple-unit train soon overheats and shuts down. Increased burden on the remaining diesels soon shut down the remaining units, like dominoes. Another problem not anticipated, the train advancing through the long tunnel creates a “piston” effect, pushing most of the air in the tunnel in front of it. This left little fresh air to cool the radiators.

Soon a steel drop door was installed at the east portal, along with two 800 horsepower electric motors driving 6-foot fans. Now when a train enters the west entrance, the door automatically drops, and the fans engage creating a near hurricane blasting past the oncoming train. Problem solved…? Not quite

An interesting problem cropped up as a result of “supercharging” the bore with air. When the door opened to allow eastbound freights to move out of the tunnel a 100-mph gale dynamited out of the tunnel, and rocks and debris were thrown in all directions. To minimize this hazard the GN blacktopped the area around the tunnel entrance. Both portals are easily accessed for viewing from US 2, the Stevens Pass highway and Forest Service roads, without trespassing on railroad property.

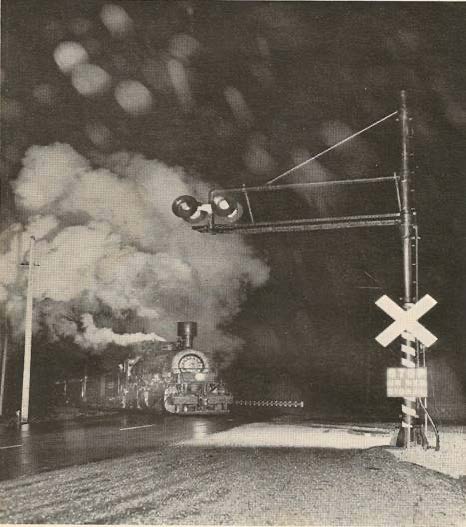

A dozen years or so back, on the quiet deck out back enjoying our coffee, and perusing the morning mail, Justine read out loud Rick Bragg’s regular piece in Southern Living Magazine. Something clicked, it read as follows: “It was in the early 1960s, in a place called Spring Garden, Alabama, where I would lie in my bed in a big, ragged house and wonder if the whole world had stopped spinning outside my window. I would have asked my big brother, Sam, about it, but he would have just told me I was a chucklehead, and gone back to sleep. I have never slept much, I think I was afraid I would miss something passing in all that quite dark. Then, sometime around midnight, I would hear it. The whistle came first, a warning, followed by a distant roar, and then a bump, bump, bumping, as a hundred boxcars lurched across some distant crossing. They were probably just hauling pig iron, but in my mind they were taking people to places I wanted to be. A braver boy would have run it down and flung himself aboard.

And then it was gone, without warning, and I would go to sleep, grudging, and dream about oceans, and elephants and trains.”

That could have been me back in the Summers of mid to late 40s, way across the country out there in Tacoma. From my large upstairs open window, or sleeping on the ground in the back yard with friends, you could hear the trains switching. The clear air resonating the sound from over 4 miles away. Sometimes it sounded like the next block over. Or maybe it was a logging train hauling empties back to the woods near Mt Rainier, with that “malley” huffing and chuffing up that 3.5 percent grade. Oh those good ole days.