A Norfolk Southern Railway Ex-NKP at Tipton IN on September 23, 2021. – Rick Bivins photo.

Union Pacific Big Boy 4014 at Ware, Illinois on Saturday, August 28th, 2021. – Photo by William Farrell

I visited Wally Watts and surprised him with chocolate and a balloon on his 91st birthday! September 18, 2021.

Ricky Bivins

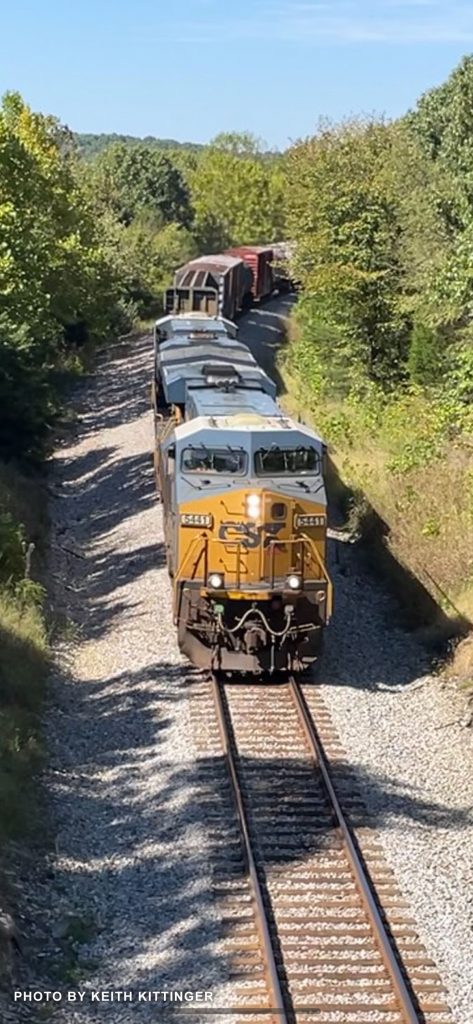

October 2004, with a full moon high in the southeast sky. There were three CSX locomotives making their way south on the main line through northern Christian County. As the trio of C-40-8’s struggled to pull their heavy load of coal south the sound of their diesel engines crackled through the crisp night air.

As the heavy train approached the East Princeton Street (Highway 800) grade crossing in Crofton. The crossing gates reacted to the CSX coal drag with red flashing lights as the lead locomotive gave a loud blast on its deep throated horn. The sound of the horn broke the roar of the diesel engines as the train passed over the East Princeton Street crossing in the sleeping rural community.

It so happens that a local resident of Crofton got caught by the lumbering train as it made its way south to unload the cars filled with black diamonds. He later reported as he sat in his car as the coal drag passed by him, he noticed a dark human like figure clinging to the ladder on one of the coal hoppers. He later remarked, “it must have been a hobo heading south to a warmer climate for the winter”.

Then with a sudden leach and the sound of twisting, banging metal the hoppers started to react violently as the sound of the coal cars slamming into each other’s couplers. The long train automatically went into emergency as a dozen cars filled with coal started to be tossed around like some child’s toys. The black cars were heaved up into the air like the wind blowing so many autumn leaves into a pile. There were cars buried half way down into the earth, while other came to rest on top of one another. Cars were bent and twisted laying on their sides with pieces of rail sticking through them like a tooth picks in a sandwich. A large dark gray cloud covered the bent and twisted cars as they oozed their valuable contains on to the track side ballast. Before the derailed cars could come to rest, they managed to takeout the newly installed but not yet operational south bound signal lights along the right of way. The sound of the grinding metal coming to a sudden stop brought many of the residents out of their track side homes to see what all the noise was about. To their sleepy, tired eyes they saw the horrifying sight of a dozen coal hoppers piled up and twisted in the late October night air. This is something you live with when your home is close to a mainline track but you never think it will ever happen to you or your community. The next morning the residents who were able to go back to sleep got up to a flurrying of activity in their town. CSX personnel along with R.J. Corman emergency railroad services had arrived sometime during the early morning. The tracks had to be cleared of all the rubble and debris that was created during the derailment. The railroad would stand to lose over two million dollars a day for each day the line remained closed. Work crews started immediately clearing the right of way as the sun was coming up in the east. Inspection teams from CSX were on hand to see which hoppers might be salvaged from the twisted mass covering the once pristine rails.

As a road foreman and his team made their way around a bent and crushed hopper, which had spilled it’s contains, they noticed a shoe sticking out from under one of the coal hoppers. Immediately they started with shovels to free the person under the mountain of black rocks and bent steel. They were to late the car had fallen on a hobo’s body crushing him. They brought in a piece of heavy equipment and were able to lift the coal car high enough to pull the man’s lifeless body out from under the twisted, jagged metal. When all present looked at the limp corps, they couldn’t help but to notice the hobo had been decapitated in the wreckage earlier that night. The county coroner arrived, took one look at the mans mangled, headless, coal covered body and pronounced him as dead. The coroner then checks the hobo’s coal dust filled pockets for identification with none to be found. In a matter of seconds, the lifeless remains would become known as, “The Headless Hobo”. Shortly after the coroner was finished with his examination. Emergency services had the man’s body on a stretcher and in the back of a pickup truck for transportation to the Hopkinsville morgue.

The word of the headless hobo spread among the crews that were working the wreckage. Everyone was told to be on the lookout for the head of the unfortunate man that was hitching a ride south with CSX. Every man working on that derailment was very apprehensive about what might be around the next pile of spilled coal. No one wanted to come up on or discover the decapitated head from the hobo. The railroad crews worked several days restoring service to the mainline in order to get it open once more. It took close to six weeks before CSX could get all the broken and derailed coal cars completely clear from the right of way.

The derailment brought people from far away just to see how horrendous and violent the incident must have been for the few seconds it lasted. During the time span of clean up, different railroad crews were on sight but no one ever found the hobo’s head. Surely it must have been buried under one of those huge piles of coal and debris that was created by the derailment. Then crushed and pushed down into the rock and soil by wheels or tracks of heavy equipment working the site. Years later motorist on highway 41, CSX locomotive engineers and Crofton locals have reported a strange sighting in the area of the derailment. These sightings can only be seen at night in the fall of the year. It appears to be a fiery ball of molten steel about the size of a basketball racing down the tracks south of the Brown Street grade crossing in the area of the fatal derailment. Many CSX locomotive engineers and conductors have seen the ball of fire out run their speeding locomotives. Then all at once it jumps over to the siding and races back up the tracks from where it started. Many people have seen this phenomenon but no one can scientifically explain what is happening out on the tracks in this little rural community. If you reunited with his body”.

The moral of this tale is, “You Can Get Ahead with CSX”.

Thomas Scott Johnson

June 2, 1949 – August 6, 2021

GREENVILLE – Thomas Scott Johnson, 72, of Greenville died Friday, August 6, 2021, at 11:35 a.m. at Owensboro Health Muhlenberg Community Hospital in Greenville. Thomas was born June 2, 1949, in Hammond, IN and was retired from Research and Development for Ahlstrom. He was preceded in death by his parents, Paul and Alice Johnson.

Survivors include his wife, Georgeann Evitts Johnson; daughter Dawn (Jayme) Grundy; son Wesley (Taylor) Johnson; grandchildren Payton Grundy, Taylor Grundy; grand-dog Molly; and sister Pauletta Dillard.

Back in the heyday of steam, several eastern railroads installed track pans.

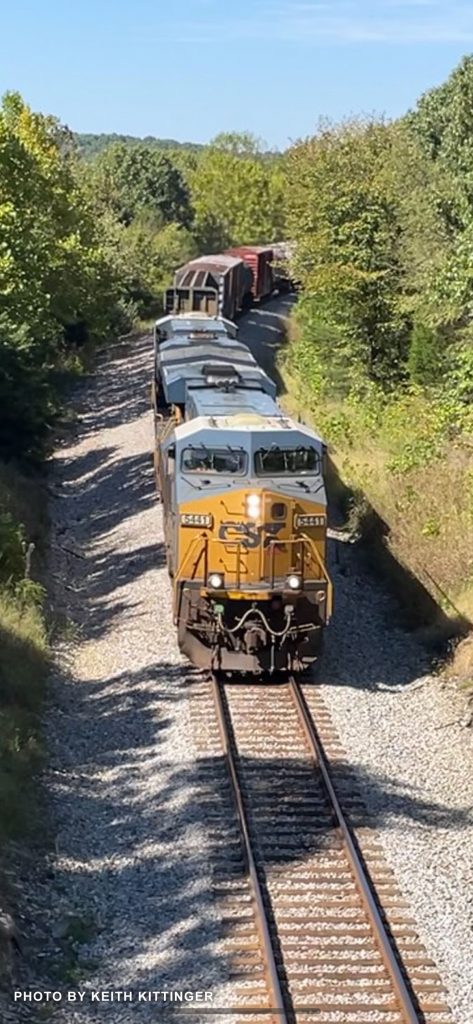

Having to stop for water was the nemesis of steam. This picture clearly illustrates the advantage. I would have preferred an image without the centerfold, but I’ve never seen a picture of trains, side-by-side taking water by track pan and water plug.

The passenger train is Baltimore & Ohio’s Diplomat rushing to Washington and St Louis in June 1944. At track speed, on a signal from the engineer, the fireman engages and air-operated scoop that fills the tank in short order from the pan between the rails.

It’s easy to see the wisdom here. The tender has an oversized coal bunker, at the expense of a limited water capacity. The Diplomat and other “scoop” trains can fly past those water plugs, saving time, not to mention the wear and tear, and energy to stop and restart a train. Lesser trains and most freights stop periodically for fuel and water, such is the case of the Reading Railroad freight train in the distance.

Installation of track pans required table-top level right-of-way. The New York Central’s 20th Century Limited on its nightly run from New York City to Chicago scooped water dozens of times, but only stopped for coal once for the entire trip. In the days before air-conditioned travel, it was wise for passengers to make sure the windows were closed at these locations, especially near the front of the train. Spray swirls from the scoop under the tender, and you can see the sky reflecting off the water in the pan at the front of the locomotive.

Gary Ostlund Credits: Ralph E. Hallock photo as seen in Classic Trains Magazine, Spring 2006

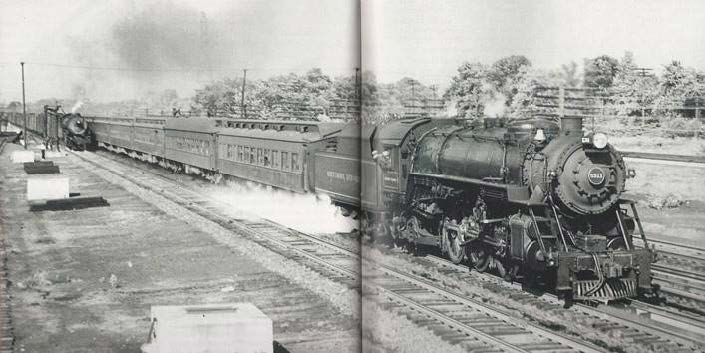

Western Montana is tough to beat for scenery, and great territory for railfans. Witness this eastbound Milwaukee freight near Tarkio. Even a large train can look rather insignificant against a rugged mountainous backdrop. A “little Joe,” one of twenty built by General Electric for Joseph Stalin’s Russia in 1948 leads three much newer GM built diesels.

The Joe packs 5,500 horsepower, each diesels add 3,000 more. The “motor” (electric engines are motors in RR lingo), was added for the climb through the Bitterroots, the Rockies and the Belt Mountain ranges. The diesels will run through to Chicago.

Little used former US highway 10 is seen below the train. The Clark Fork River begins near Butte and drains into Lake Pend Oreille (Ponderay) in Idaho. The river, continues through N.E. Washington as the Clark Fork or the Pend Oreille River (depending on which map you use), to the Columbia, just inside Canada at a town appropriately named “Boundary.”

Out of the picture and across the river is Interstate 90 and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe rails of the former Northern Pacific. The NP and Milwaukee crews could see each other for many miles passing through Montana. In many places they were side-by-side, somewhat like double-track.

This scene captured by Robert F. Wilt in July 1973, graced the Milwaukee Railroad Historical Association calendar for June 1992. Thirteen months later the electrics dropped their pantographs for the last time. Seven years hence the railroad ceased to exist west of Minnesota. – Gary Ostlund

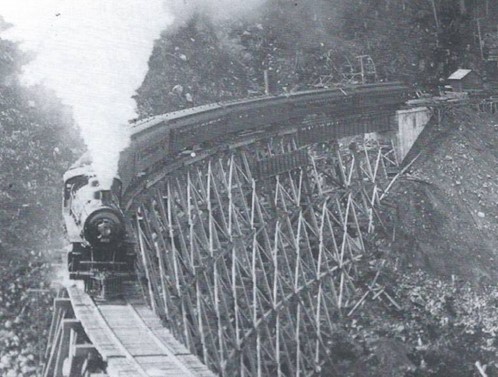

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

In their rush to build westward, the railroads built some pretty substantial wooden bridges across chasms and watercourses. Timber was readily available and cheap, and steel was out of the question at that time. After the railroad’s “Last Spikes” were driven, and the bottom line improved, so did their rights-of-ways. The Milwaukee was the late-comer to extend their reach toward the Pacific Northwest, thus their route choices were made after two other major railroads built their lines across the same prairies and mountain ranges.

One could argue that you are viewing the same bridge, years apart. But, from the mid-teens, (the main picture), to the modern era a lot tree growth and foliage would have transpired. Also, the Milwaukee bridge design is pretty standard. There are five steel trestles in about a twelve mile stretch of rail-line leading to the 2-mile tunnel under Snoqualmie Pass. All five are curved in the same manner as these examples. You can see four to this day from your drive over Interstate-90.

Looking closely at the wooden trestle, you’ll see there are steel uprights inside the framework of the bridge. The first and second girders are set in place and the third has been lowered, temporarily secured, while an eastbound passenger train charges past. Earthen fills were used when conditions permitted. Factors included the height, and volume of the water-course being crossed, and availability of nearby fill material. Numerous lesser creeks were filled in the manner shown above, always the first choice when practical.

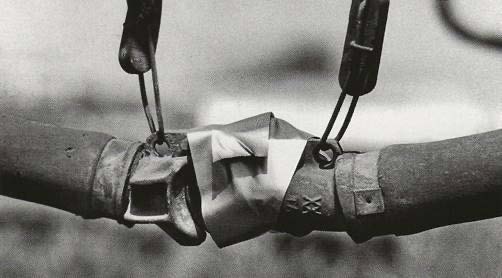

Today railroads spend millions of dollars on ribbon rail, expensive locomotives, cutting edge communications among other business needs. But there’s still a place for a roll of handy-dandy duct tape. Many uses, as you can see one

example in the picture above. In this case, if air pressure is not maintained in the “trainline” as it’s called, the brakes take hold. Less than 50 cents worth of tape will help keep the hose connections from parting. Air hoses for the

braking system, like those above are found just below the coupler connecting every car in a train.

Many experienced operating train crewman (or woman), pack around a roll, finding a wide variety of uses: 1) weather-stripping around damaged or ill-fitting cab doors on locomotives. A skilled crewman will apply it in a manner that would allow the door to be opened and closed without tearing or pulled loose. 2) It works nicely holding paper towel in fashioning a sun visor. 3) An ample amount will even seal a broken trainline to seal a crack. 4) It makes a great shade on a cab light. 5) Duct tape will cover holes in the cab walls to block the cold air from coming in.

George Westinghouse received a patent in 1869 for the Air Brake system, a live-saving invention. His air-brake system, adorns every rail car to this day. Little did he know he would get help from an everyday item from the hardware store. Gary O. Ostlund

September 9, 2021, and CSX GP38-2 2806 arrives in Mitchell, Indiana with a rather sparse two-car local J780. The crew will tie down for the day and hopefully have m o r e L e h i g h Cement loads for the eastbound trip to North Vernon the next day.

Consolidated Grain and Barge GP9 6140 shuttles CSX covered hoppers for loading at Olney, Illinois on

September 8, 2021. Later in the day CSX AC4400CW 231 and ES44AH 761 will haul the train east to

Vincennes, Indiana and then points south. – Photo by Chris Dees

At JO Tower in Seymour, manifest Q688 (Louisville to Indianapolis) waits for the track gang and signal department to finish up PTC installation work on September 9 , 2021. Once cleared, the train will continue its northbound journey over the Louisville & Indiana Railroad. Photo by Chris Dees

Below, a UP Northbound Stack Train is on a roll through Scott City, Missouri on the

morning of August 29, 2021. The last shot of UP 4014 was made as it crossed over the Kaskaska

River just north of Chester, Illinois on the afternoon of August 29, 2021 Photos by

Bill Grady Photo by Bill Grady

We express our sorrow in the passing of Shirley May Hinrichs, wife of long-time WKNRHS Chapter member Chuck Hinrichs, on Monday September 6, 2021.

Shirley May Hinrichs, 90, of Hopkinsville, KY died at 10:39 p.m. Monday, September 6, 2021 at her residence.

Graveside services will be 12:00 p.m. Friday, September 10, 2021 at Kentucky Veterans Cemetery West with the Rev. Dan Huck officiating. Visitation will be Thursday from 4:00 – 7:00 p.m. at Hughart, Beard & Giles Funeral Home. Hughart, Beard & Giles Funeral Home is in charge of the arrangements.

A native of Baltimore, MD she was born March 5, 1931 the daughter of the late Norman E. Bolander and Jennie Violet Fowler Bolander. She was a devoted wife and loving mother. She was a member of First United Methodist Church. She was an avid bowler, golfer, bridge player, and gardener.

In addition to her parents, she was preceded in death by her son: “Brian” Charles Hinrichs; and her four brothers.

She is survived by her husband of 67 years: Charles “Chuck” Hinrichs; her children: Debi (Ray) Anderton, Gretchen Edwards, and Roger Hinrichs all of Hopkinsville, KY; her eight grandchildren: Trevor (Kelly) Dunham, Peter Roshell, Jennie Jenkins, Kayla Hinrichs, Hunter Edwards, Kendra Chesser, Casey Hinrichs, and Kati Hinrichs; and six great grandchildren.

Memorial contributions are suggested to Pennyroyal Hospice 220 Burley Avenue, Hopkinsville, KY 42240.

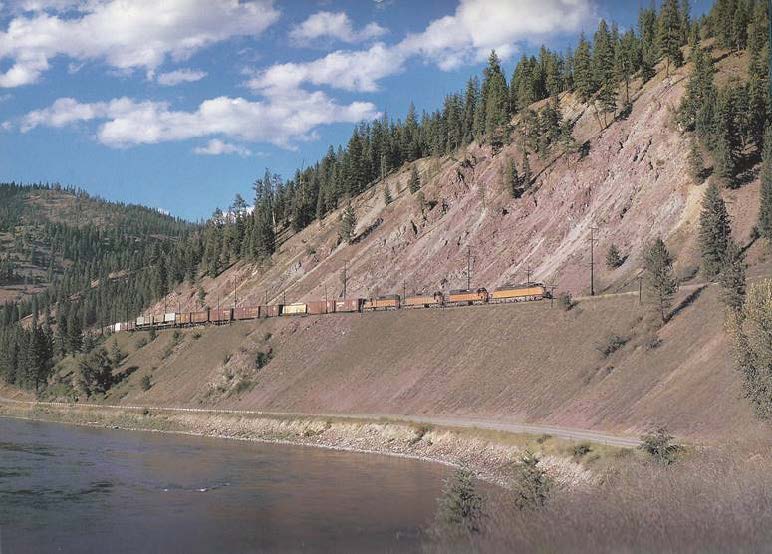

The time is 12:30 PM on October 13, 1949. We’re inside Mission Tower, half a mile out of Los Angeles Union Station, watching Southern Pacific train 4, the Golden State (left) and Santa Fe 20, the Chief, departing simultaneously for Chicago. It looks like a race, but it’s not really much of a contest: The Chief, running on Santa Fe all the way for 2,224 miles, will beat the Golden State (2,268 miles on the SP and Rock Island) to the Windy City by about 7-3/4 hours.

The Chief will cross Cajon Pass to Barstow and shoot east across northern Arizona to Albuquerque, NM, then northeast over two mountain passes, and cut through the southeast corner of Colorado. After a stop in Dodge City and a few others, it will aim for Kansas City. Cutting through the SE corner of Iowa, crossing the Mississippi River, it will visit some cities in Illinois before arriving at Dearborn Station, one of seven railroad stations in Chicago.

The Golden State exits California near Yuma, does a bee-line for El Paso, then NE through New Mexico to Tucumcari. There the Rock Island takes over touching a bit of Oklahoma, slicing through Kansas to Topeka and on to Kansas City. Then the GS treks through a corner of Iowa, zips through the Quad Cities. On through the corn fields of Illinois, it completes its trek at LaSalle Street Station, only a few blocks from Dearborn and the Santa Fe.

There were other passenger trains that competed head-to-head, mainly the New York Centrals 20th Century Limited and Pennsy’s Broadway Limited. They raced out-of-Chicago, on parallel tracks, for many miles in their quest to get their patrons to New York City, fast. That daily race was a little more even-handed. The New York Central route to the Big Apple was 960.9 miles, with mostly water level terrain. The Broadway’s routing was only 908.2 miles, but included scaling the Appalachian Mountains in Pennsylvania. Wikipedia states that both of these luxury trains completed their task in about 16 hours. The green hat crowd and the red hatters probably will never agree on that.

Credits: First paragraph verbatim in Classic Trains Magazine, Spring 2021

Submitted by Gary O. Ostlund

I spotted this little jewel at Holiday World Splashing Safari last month as I aided our Youth Minister on a Youth outing. After researching (Googling) it, I found it was the first ride in Santa Claus Land Railroad (later to be Holiday World). The locomotive was restored and placed on display to celebrate the park’s 70th birthday this year. You can watch a time-lapse video on YouTube of the painting: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kNdeiWlIej8. Ed. Bill Thomas

For more information and registration go to the NRHS’s website: https://admin.nrhs.com/public/